UN COUP DE DÉS

text by David Dernie

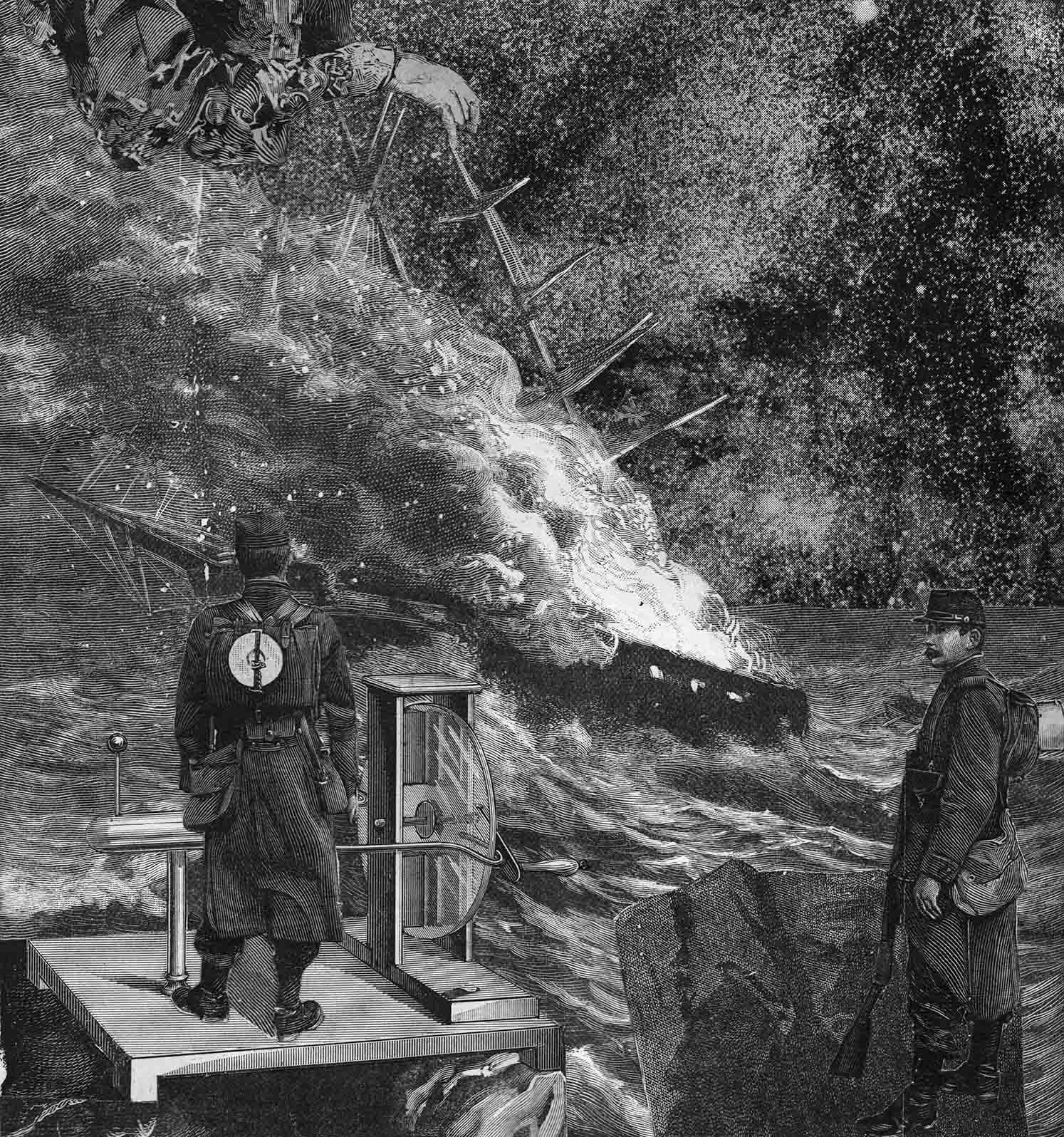

The aged, off-white paper had become dry, frail, yellowed, but its text framed engravings of exceptional quality

These collages are made by hand from original copies of the French newspaper La Grande Illustré (1904) whose engravings are a snapshot of the terrible uncertainties, reported disasters and social unrest that coloured French life at turn of the century.

The work set out to explore questions relating to history and to its visual documentation and mediation. It considers the construction of actual histories, first through attention to the newspapers’ engravings that were produced at an industrial scale, based on correspondents’ accounts or sketches of events — mostly not witnessed directly. It also reflects on paper technologies by reconstructing ‘fictive histories’ as collage. It inquires of the boundaries between actual and re-imagined histories, between historical facts and constructed realities. It opens up questions about history, media and image.

The newly configured paper images come together as a collage novel. Each collage is comprised of intricate layers of smaller pieces of newsprint that are glued together to form almost seamless images that blur the boundaries between the re-imagined histories and actual events.

Un Coup de Dés originated when I found a collection of old newspapers in a bric-a-brac market in southern France. A stack of aged newsprint appeared like a material metaphor for a distant past: it was a magical collection of La Grande Illustré dating from 1897. I did not know what lay ahead, I had no idea of how much time I would spend working with them over the next few years.

The aged, off-white paper had become dry, frail, yellowed, but its text framed engravings of exceptional quality. They spoke of dramatic conflicts and often tragic events. Bringing the world to France, the paper’s engravings were made from sketches or written accounts passed on from correspondents in Africa, India and the Far East. They captured the mechanical apparatus of industrialized nations, framed expressions of a fraught age: distant peoples, exotic seas, wastelands, conflicts, politics, industrial machines, personal tragedies — and shipwrecks.

And in the image of the shipwreck, of vessels tossed mercilessly on raging seas, lies a central leitmotif of the age — of the ‘cultural shipwreck’ that was the twilight years of the decadence in French culture, a world that had been finely crafted by the early poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé (Pierrot, 1981). Springing from Baudelaire and drawing on poets such as Verhaeren and Rodenbach, the artists Khnopff and Mellery, and in the wake of the new science of psychology, Mallarmé established the notion of the ‘symbolist interior’ as retreat from the industrialized world, or chambre rêve (Silverman, 1989). These ‘dream spaces’ appear repeatedly in the literature, visual art and art nouveau architecture of the period, as images of exotic greenhouses, diving bells, aquaria, crystalline interiors or the mist-filled plains of Flanders.

Mallarmé’s later poem Un Coup des Dés (A Throw of the Dice, 1897) lends its title to, and indeed inspired, the textures and structures of my own collage novel. The poem represents a radical turning point in the solipsistic world of late nineteenth-century decadent aesthetics and is remarkable for its revolutionary use of language, and of paper space. Words flow across the pages, seemingly at random, creating clusters of phrases and imagery, which nevertheless throw up no overall narrative. Its opening theme ‘shipwreck’, reflects the deep malaise of fin-de-siècle culture, suffocated by the shackles of tradition and disoriented by industrial change.

Shipwrecks, literal and metaphorical, appear repeatedly in the newspapers and is a resonant impulse in the collages. And as for Mallarmé’s poem, the materiality of the paper and the crafting of its newly choreographed surface mattered. The making of these papiers collés was slow. Rabbit skin glue was the most delicate accompaniment to the newprint’s delicate and enduring surface. There was no preconceived narrative, or structure. Rather the work was driven on the one hand by the impulse of the existing paper images — by chance — and secondly by the process of the making itself. The work was shaped out of circumstances for which I wasn’t entirely responsible.

Details, textures, forms were carefully cut out with a 10A scalpel blade, disassembled and reassembled. They were reshaped into composite engravings of an altogether fictive history. However unlikely these are as illustrations of actual historical events, their detail, material quality and crafting create convincing, almost seamless new ‘editions’ of the original engravings; so much so that they have an authority — or integrity — to sit alongside that of the newspaper’s illustrations. Together they are two versions of imagined histories, one illustrated (as imagined) and then remediated, reconfigured as in a dream. After all, weren’t the original engravings also imagined or even altogether invented? How for instance, did the Parisian engravers know what a shipwreck on the Nile, or a balloon flight over Crimea really looked like? Both images, the collage and original engraving, are in fact as close to dreams as they are historical ‘fact’. One assumes the authority to account for history as ‘illustrations’, the other is a deliberate fiction. And as such, their resemblances — embodied in the continuities of themes, forms and material textures within the paper medium — open questions that belong to the mediation and configuration of histories.

This collection of collages comes together in the form of a collage novel and may be associated with a wide range of artists’ books and other forms of graphic novels – and other forms of novels – that take collage or found language as a mode of writing (Pulsford, Wolfram, 1978). Collage as a technique emerged in the early decades of the twentieth century, as artists explored non-perspectival space, time and movement in the visual arts – the experience of seeing – rather than the seen. From the experiments of cubism, and later Parisian surrealism, emerged the collage novels of Max Ernst (Spies, 1988). Often using reconfigured engravings Ernst illustrates the power of collage to communicate non-visual, or temporal themes. Ernst’s reconfigured engravings are a close companion to my own collage novel, due to the similarity of the source material, but otherwise any connection is unintentional. Like Ernst and many of the broader tradition of collage novels, there is a non-linear structure to my work. There is no overarching narrative, but all narratives are available to the reader, all possible connections and dislocations. What drove the work was work itself, and what drives its meaning is simply the seeing of the imaginative reader.

A selection of these collages was exhibited at the Ruskin Gallery, Cambridge (2016) in collaboration with the author Olivia Laing whose text accompanied the work. To mark the exhibition, the full body of these images was published in Shipwreck, (2016)